How the Golden State Shaped the Vice President

Written by WALTER KAWAHARA

Graphic by MATTHEW WILLIAMS

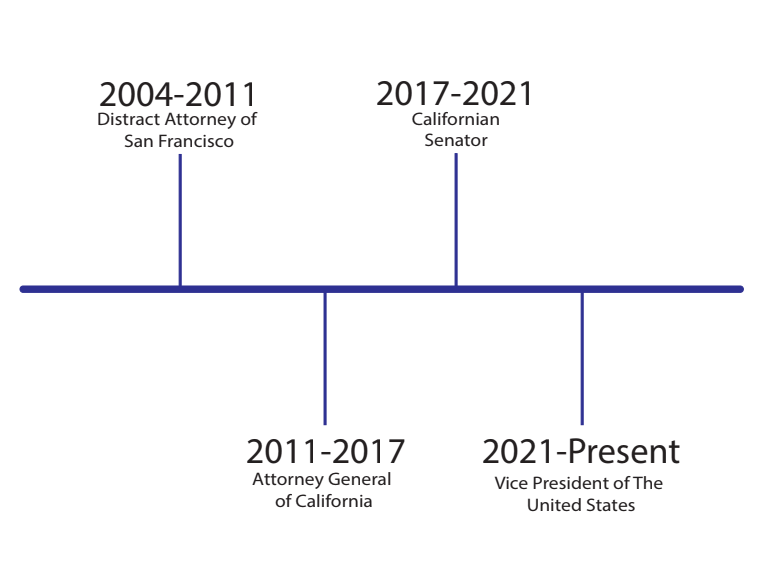

//As the American public gets to know Kamala Harris this election season, Bay Area voters can say they have a head start. While Harris has held national office for three–nearly four–years as Vice President and an additional four as a United States Senator, her record in California goes back twenty-one, when she ran and won a race to be the District Attorney of San Francisco. A lot has changed over those twenty years, not least of which being Harris. But how exactly did the Presidential Candidate navigate the evolving political mores of the day, and what does that say about how she may govern?

In California, now-Vice President Kamala Harris has been an ever-strengthening political force since 2003. Her “smart on crime” rhetoric and “for the people” mantras have found a ready audience, but beyond the three-word slogans, Harris has changed and left many a befuddled voter along the way.

Kamala Harris was born in Oakland, California, in 1964 to parents Shyamala Gopalan and Donald Harris, both graduate students at U.C. Berkeley. Shyamala Gopalan was an immigrant from India, and she went on to become a breast cancer researcher. Donald Harris is a Jamaican immigrant who became an economics professor at Stanford University. Despite her parent’s prestigious vocations, Kamala Harris has spent much of the campaign boosting her middle-class bona fides; Donald Harris, who the British publication The Economist described as a “combative marxist” economist, left Shyamala Gopalan when Kamala Harris was seven years old, and her mother raised her and her sister as a single mother. As a young adult, Harris received a Bachelor’s Degree from Howard University, a Historically Black College, and received her law degree from the Hastings College of Law, U.C. Berkeley, before starting her career.

After college, Harris became a prosecutor in the Bay Area. By the 1990s, Harris had already started operating in the political spheres of the region, where she became familiar with influential donors, established politicians–including Willie Brown, whom she briefly dated–and up-and-coming politicians like Gavin Newsom. These connections would prove pivotal; Brown secured several state board appointments to Harris and the large network of socialites she had become known to would help finance her bid to challenge incumbent San Francisco District Attorney Terence Hallinan in 2003.

Terence Hallinan was an enigmatic figure in his own right. Born to a wealthy family, he ran into the law several times in his youth for brawling. As a District Attorney, Hallinan undertook a historic diversification of the San Francisco District Attorney’s office and refused to pursue the death penalty. When Harris challenged him, one of her primary attacks was that he was not tough enough on crime, citing Hallinan’s low conviction rate–though Hallinan and his supporters pointed to a decline in violent crime in the city as evidence of his effectiveness. Given the left bend of San Francisco, Harris walked a political tightrope and called herself a “progressive prosecutor”. In the end, she easily beat Hallinan with 56 to 44 percent of the vote.

From there, Harris would serve two terms, win and serve one and a half as Attorney General of California and win and serve four of a six-year term in the U.S. Senate. Most of this period featured the political pragmatism that got her first elected, taking a strategic combination of progressive and moderate positions. While campaigning, Harris has frequently mentioned her role in getting a $20 billion settlement for California homeowners following the subprime mortgage crisis as California Attorney General, but she rarely mentions her successful push to make school truancy a misdemeanor. When Harris was elected to the Senate in 2016, however, her political universe was flipped upside down by the election of Donald Trump to the Presidency.

Starting in 2017, the progressive wing of the Democratic Party was on the rise. It was fresh off the heels of a surprisingly strong primary campaign by Vermont Senator and self-identified Democratic Socialist Bernie Sanders in 2016 and a growing discontentment with the moderate–at times conservative–direction the Democratic Party had adopted under Bill Clinton in the 1990s. The Democratic Party, so the media narrative went, was at war. Harris sided with the progressives.

Come 2019, Harris joined the crowded field to be her party’s nominee for President. Although she was considered a promising candidate, her campaign was immediately challenged by the question of ideological direction. Harris ran as a progressive, but not as far to the left as candidates like Sanders, yet she was not moderate enough to attract the voters who gravitated toward Joe Biden. In the political crosshairs and facing dwindling campaign funds and poor polls, she dropped out before a single primary contest.

In the end, it appeared the progressive wing of the party had overestimated its support. At the time, over half of Democrats considered themselves moderate, and a little less than ten percent qualified themselves as conservative. The working-class voters that Sanders had presumed would propel him to victory sided with the more culturally palatable Biden, and he landed the nomination. Harris had had a limited relationship with Biden at this point, and the key moment of her campaign was debate criticism of his 1970s opposition to busing that benefited her. Regardless, Biden liked Harris on a personal level; both she and Biden’s now-deceased son Beau had served as their states’ Attorneys General together. He chose her to be his Vice President.

Upon entering office four years ago, the Biden Administration was saddled with numerous issues; the COVID-19 Pandemic, a flagging economy and a destabilized world stage. Though the Biden Administration, with the help of Harris’ key vote as Vice President in an evenly split senate, was able to pass several significant pieces of legislation, including the American Rescue Plan, a stimulus bill to boost the economy, the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act and the CHIPS Act to reinvigorate American infrastructure and manufacturing and the Inflation Reduction Act to reduce healthcare and energy prices and boost America’s green energy industry, and led the international community’s response to the Russo-Ukrainian War, it has been saddled with historically low approval ratings owing to high inflation, illegal immigration and the chaotic 2021 withdrawal of American forces from Afghanistan.

Harris, in particular, was subject to intense criticism. As Vice President, she had a contentious relationship with the press and was noted for her “word salads.” Her office’s staff changed numerous times, and there were rumors of an unhealthy work environment. Harris reportedly watches the show Fox & Friends, and its negative coverage of her supposedly caused her some distress. With historically low approval ratings, Harris made appearances rarely.

With these frustrations remaining steady through Biden’s term and growing concerns about his mental acuity, the President trailed his opponent, Donald Trump, consistently in polling, with the Trump campaign reportedly planning on winning the election in an Electoral College landslide. These issues all culminated in what was arguably one of the worst nights of Joe Biden’s political career: the first presidential debate. Throughout the debate, Biden often spoke haltingly, lost his train of thought and struggled to contain his lifelong stutter. The campaign later said that the President had had a cold, but Biden had, in effect, lost any chance of winning the election that night. On July 21, Biden released a statement that he would drop out. “It has been the greatest honor of my life to serve as your President. And while it has been my intention to seek reelection, I believe it is in the best interest of my party and the country for me to stand down and focus solely on fulfilling my duties as President for the remainder of my term,” wrote the President in the digital press release.

From there, the Democratic Party quickly chose Kamala Harris to be the party’s nominee. By August 2, Chair of the Democratic Party Jaime Harrison had announced that Harris had acquired enough delegates to win the party’s nomination. The Vice President, who had once been so unpopular that a commonly suggested treatment for the ailing Biden campaign was dumping her from the ticket altogether, was received at first with tentative relief by a party that had spent the preceding months coming to terms with a second Trump Presidency, and then, as polls and media narratives started to shift, with exuberant enthusiasm.

Harris emphasized optimism, potential–and even the possibility of bipartisanship. Under a Harris Presidency, her campaign said, America would turn a corner. A shift in not only the Democratic Party, but in the United States’ general electorate, occurred. While Biden trailed Trump narrowly in the popular vote and badly in swing states, Harris has consistently held a small lead nationally and remained neck-and-neck with the former President in the key swing states of Pennsylvania, Wisconsin and Michigan. “I feel more confident now than I did 60 days ago for Democratic wins at the national level (White House, Senate and House)” said Katie Ricklefs, Chair of the Contra Costa County Democratic Party (CCCDP) in a digital correspondence with The Page. But Presidential Elections are not won on good feelings alone, and many feel that Harris has been lacking in the hard facts of policy that can carry a candidate over the finish line “I don’t actually know much about Harris’s record, but she seems nice” said Gavin Mallari, a sophomore at Las Lomas, in a survey conducted The Page staff.

During her time as Vice President, Harris had a brief recess from ideological scrutiny. As a Vice President, Harris’ positions on the issues were Biden’s positions on the issues. But Biden and Harris are fundamentally different people. Biden is the last vestige of the New Deal Coalition of the Democratic Party, an Irish Catholic man from a lower middle-class Pennsylvania family. He leaned heavily on economic populism throughout his career and as President. The President was pro-union, increased Trump’s tariffs on China and supported increasing taxes substantially on wealthy Americans and big corporations. As a presidential candidate, however, Harris has significantly toned down these elements of the campaign. Her messaging focuses more on the consumer than the worker, with a strong emphasis on the cost of living, and she has redoubled the party’s outreach to the Silicon Valley donor class.

Harris has no true faction of the Democratic Party. She is not a progressive stalwart like Bernie Sanders, nor a lunch-pail Democrat like Biden and she does not not quite fit the mold of technocratic moderate that figures like Hillary Clinton do. So who is Kamala Harris? She is a middle class daughter of immigrants and Oakland, a pillar of San Francisco’s wealthy social scene and a friend of Silicon Valley; she is a progressive prosecutor and a pragmatic politician. Kamala Harris’ life and career is the realization of the California Dream. But California is a state of complexities, and if voters wish to best understand the woman who could be their President, it is incumbent they understand the state that made her.

Leave a comment